We've looked a lot at the subject concords in Giriama, saying they were similar to English pronouns. Now we finally get to real Giriama pronouns.

Copula 3: being something

In this previous post, we looked at how to say "I am [somewhere]", "I am at". In this post, we will look at how to say "I am [something]", "I am".

Nouns: Class 3 and 4

In this post, we will put together some full sentences involving mu/mi nouns, like mwezi and mwaka.

Counting 1: months and years

We've seen the numbers in Giriama before, but because Giriama has noun classes, the numbers change depending on what you are counting.

In this post, we look at counting miezi, months and miaka, years, which are from Class 4: mi-. (Class 3, mu-, in the singular: mwezi and mwaka.)

In this post, we look at counting miezi, months and miaka, years, which are from Class 4: mi-. (Class 3, mu-, in the singular: mwezi and mwaka.)

Tenses 4: á, the distant past

We have looked at -dza-, the tense used for things which happened today. In this post, we will look at -a-, the tense used for things which happened longer ago.

Possessives 1: Class 1 and 2 (people)

The Giriama word for my is -angu. The dash at the front means that there is something missing: in Giriama, the possessives - my, your, his... - have to agree with the noun. Each noun class has a different consonant which goes at the start.

Tenses 3: dza, today's past

The past tenses in Giriama do not correspond exactly to the past tenses in English.

Pronunciation 5: fricatives

In this post, we look at the buzzing, hissing sounds of Giryama - the fricatives.

Tenses 2: ku, the infinitive

In this post we will look at the infinitive form of the verb, which starts with ku-. This is the "to -" form in English.

It is used in phrases such as:

I like to go to the beach.

I am able to read.

I start to eat.

It can often be translated into English with a gerund, or -ing form:

I like going to the beach.

I enjoy reading.

I like eating.

It is used in phrases such as:

I like to go to the beach.

I am able to read.

I start to eat.

It can often be translated into English with a gerund, or -ing form:

I like going to the beach.

I enjoy reading.

I like eating.

Review 1

So far in this blog, we have covered:

- Pronunciation of vowels, nasals, stops and r

- Subject concords: how to say I go, she goes, we go...

- Object concords: how to say I like him, you like her, we like them...

- The na tense: how to say I am going, he is going...

- How to count from 1 to 10

- How to ask yes-no questions

- How to ask Where?

- What Bantu noun classes are

- Class 1 and 2 nouns: some people words

Pronunciation 4: stops

'Stops' are sounds where you completely stop air from coming out of your mouth. Giriama has 12.

Nouns: Class 1 and 2

We've introduced the concept of noun classes in a previous post. In this post, we will work through examples from classes 1 and 2.

Noun classes

In this post, we will attempt the most novel bit of Giriama grammar, as far as English speakers are concerned: the Bantu Noun Class System.

Questions 2: where

In this post, we will start looking at question words. We start with hiko, meaning where.

Object concords 2

Today we will look at those object concords which are not the same as their subject counterparts: you, him, her and them.

Object concords 1

By now, you are hopefully familiar with the subject concords of Giriama: ni-, u-, a-, fu-, hu-, mu-, ma-.

You can form very simple sentences such as ninashoma, 'I am reading', or anenda, 'he is going'.

But how do you say something like 'I see him'?

You can form very simple sentences such as ninashoma, 'I am reading', or anenda, 'he is going'.

But how do you say something like 'I see him'?

Questions 1

Yes-no questions

As in many languages, you can ask yes-no questions in Giriama just by changing your tone. Simply make your statement - unenda, you are going - but rise in pitch on the last syllable - unendá?If you want to be extra clear that it is a question, say "vidze" at the start of the phrase:

| Vídzè, ùnèndá? | So, you're going? |

| Vídzè, ùnàryà màízú? | So, you're eating bananas? |

| Vídzè, ànàhèndzà màízú? | So, she likes bananas? |

Pronunciation 2: nasals

Today, we are looking at the nasal sounds of Giriama. These are the sounds made by air coming out of your nose, but not your mouth.

Tenses 1: na

Today, we are going to learn how to include tenses with our verbs - to talk about things that happened in the past, are currently happening, or will happen in the future, as well as things that usually happen.

Subject concords 2

In Part 1, we looked at the Giriama words for I, you, he and she. In this post, we will look at the subject concords used for we and they.

Subject concords 1

The subject is the part of the sentence which is doing the action: I read, you dance, Chengo sleeps.

In English, the subject is a separate word (called a pronoun). In Giriama, as in Swahili and other Bantu languages, the subject is attached to the beginning of the verb (and called a concord).

Pronunciation 1: vowels

Vowels

Unlike in English, the vowels are pretty simple. There are 5 of them, and they are pronounced similarly to the vowels of Swahili or Spanish.

Welcome to Teach Yourself Giriama!

A few facts about the Giriama language.

|

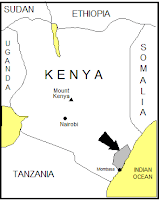

| Map of Kenya showing the location of Giryama speakers From The Verbal Morphology of Kigiryama - see Resources |

It is a Bantu language, related to Swahili, with perhaps 60-70% of Giriama words coming from the same roots. (For comparison, the same source puts English as sharing 60% of its vocabulary with German. French and Spanish share 70%, Spanish and Italian share 80%, and Spanish and Portuguese share 90%.)

You will also see the language name written as Giryama or Kigiriama. 'Ki' is a prefix (more on these in future) which in this case is used for languages. So Kigiriama means 'language of the Giriama', just as 'Kiswahili' means 'Swahili language'. You don't need to use the 'ki' when talking about the language in English - it's nothing to do with respect, it's just a grammatical thing, which is meaningless in English.

Its writing system is based on the Latin alphabet, just like English and other European writing systems, and most other Bantu writing systems. However, it does not seem to be very widely used. As far as I can tell from abroad, there are very few publications in Giriama. Most (?) higher education is in Swahili or English; if you are well enough educated to want newspapers, novels and textbooks, you will be able to read the existing Swahili ones, so there appears to be little demand for Kigiriama publications at present.

See Resources for what I have been able to get hold of so far.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)